For years, I drove past Joe Beef Park without ever stopping to think about the name. Like many people, I assumed it was a casual reference to the famous Montreal restaurant and kept moving. Then one small realization changed how I saw the space. The park was not named after a place, but after a person. Joe Beef, born Charles McKiernan, was a real figure whose influence once shaped Montreal’s working-class history. Suddenly, the park felt different. Beneath the laughter, sprinklers, and worn grass was the memory of a man who mattered deeply to the people who built this neighborhood. He was not a brand or a clever nod. He was a presence in a city defined by labor, struggle, and resilience. That is why, when chefs David McMillan and Frédéric Morin named their restaurant Joe Beef in 2005, it felt less like marketing and more like a tribute. The restaurant’s rustic, meat-driven, no-nonsense style reflects the spirit of McKiernan’s original canteen, carrying forward his values of generosity, honesty, and community in a way that still feels alive.

In 1868, McKiernan opened his canteen near the Lachine Canal, and it quickly became far more than a bar. It served as a soup kitchen, a bunkhouse, and a gathering place where sailors, longshoremen, immigrants, laborers, and the overlooked could eat, talk, argue, and organize. Known as the working man’s friend, Joe Beef fed the hungry, sheltered the outcast, and welcomed anyone who crossed his threshold. In a neighborhood with few public spaces, his tavern became a social anchor. It offered more than food and drink. It offered belonging, a sense that someone was looking out for you when few others were.

Joe Beef stood apart because he chose care over punishment. When trouble arose, he was more likely to offer a meal or a job than call the police. He believed order came from compassion, not force, and that belief earned him fierce loyalty among working people. To city officials, however, his canteen was a problem. Loud, political, crowded, and unapologetically working class, it drew constant scrutiny. Joe Beef was frequently dragged into court over liquor licenses, noise complaints, and incidents tied to his tavern, and he regularly bailed out patrons who ran afoul of the law. Rules mattered less to him than people, especially when regulations stood between a hungry man and a warm meal.

That outlook placed him at the heart of the 1877 Lachine Canal strike, one of Montreal’s most significant labor disputes. During the winter expansion of the canal, contractors exploited seasonal unemployment to slash wages and impose brutal conditions on a workforce made up largely of Irish immigrant laborers. The workers demanded one dollar for a nine-hour workday, a modest request given the danger of the job. Joe Beef became one of their most visible supporters. His canteen turned into a hub for survival and organizing as he fed hundreds of striking workers daily with bread, soup, and tea, even supplying food to the soldiers guarding the canal. The first public strike meeting took place outside his tavern, where he urged thousands of workers to stand firm while keeping order. Although the strike collapsed after eight days, it drew attention to labor abuses and helped weaken exploitative practices like company store payments.

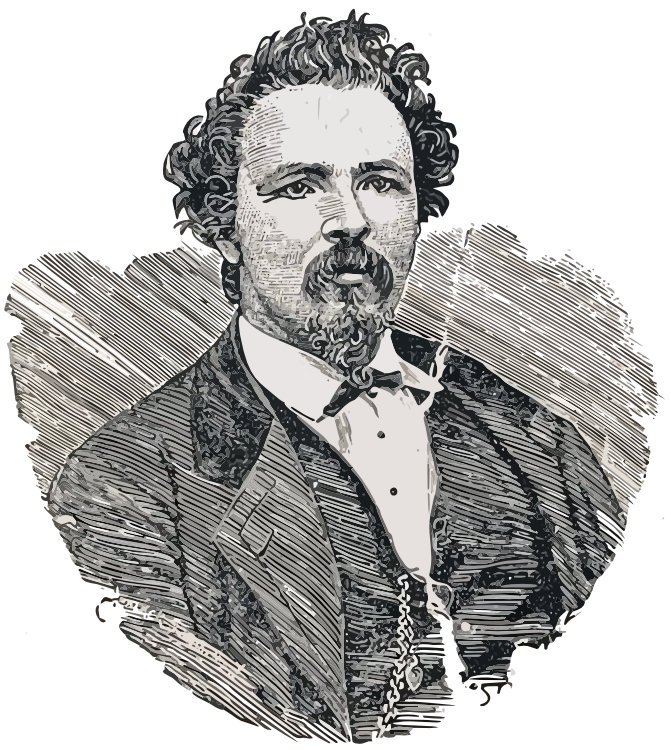

Stories followed Joe Beef everywhere, including the famous tale that he kept live bears in his basement. Whether fact or folklore, the story captured the wild, defiant spirit of the man and his tavern. Respectability never interested him. When he died in 1889, his impact was undeniable. Workers walked off the job to attend his funeral, following his hearse through the streets of Montreal. No confirmed photographs of him exist, only engravings and later interpretations, which only deepen the legend.

Today, Joe Beef Park in Pointe Saint Charles is a modern gathering place. Children play where workers once gathered. Families meet where arguments, ideas, and solidarity once filled the air. With play structures, splash pads, and a mini soccer field, the park quietly continues Joe Beef’s tradition of bringing people together. It is a reminder that history does not always announce itself. Sometimes it waits in a neighborhood park, asking us to slow down, look around, and remember who stood here before us and why their story still matters.